Development organizations embrace micro-services as a scaling architecture pattern. They also have to provide access to their systems thru various interfaces - desktop, mobile web, mobile applications and various third parties thru APIs. Designing a convenient access architecture is challenging, especially when you also have some legacy systems and services to talk to. Let’s take a look at one design pattern, which can help.

Monolith, but for interface

I am drawing from experiences I see during my occasional consulting gigs, especially in retail and e-commerce organizations, but I suppose it’s the same everywhere. As these companies look at multi-channel strategies, they realize they will need a multitude of customer interfaces with their specific needs, but all of them must draw from the same data. This logically leads to a service oriented systems design. The general idea can be, for example, to build a separated product catalogue, which will provide product info to all other systems.

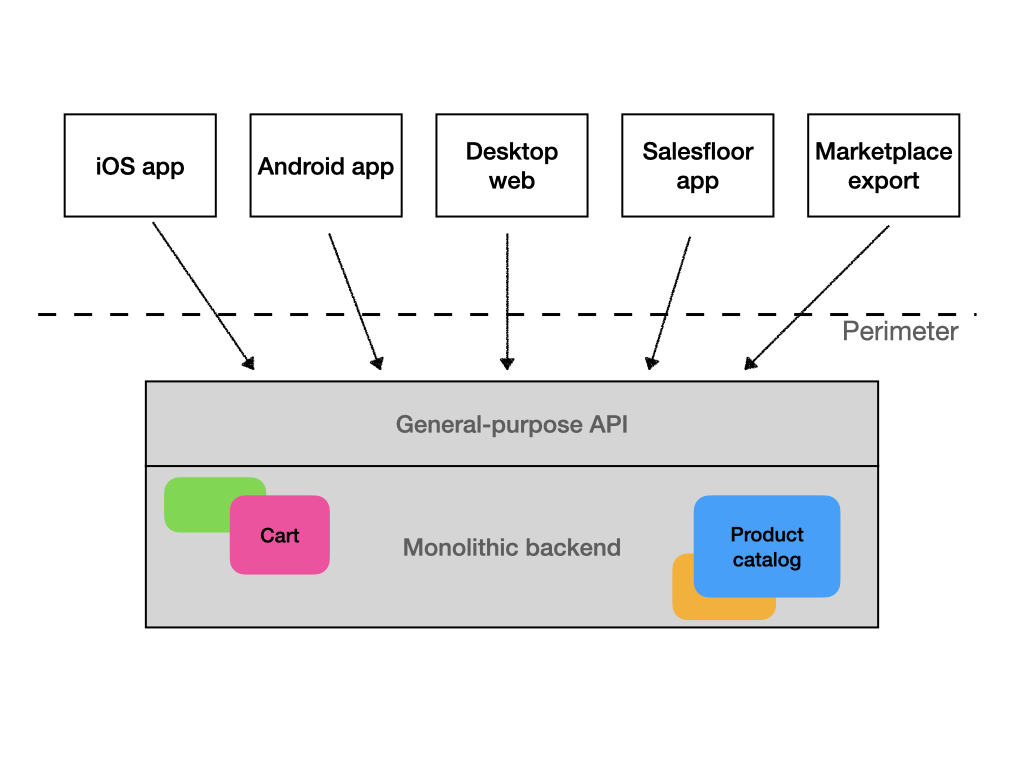

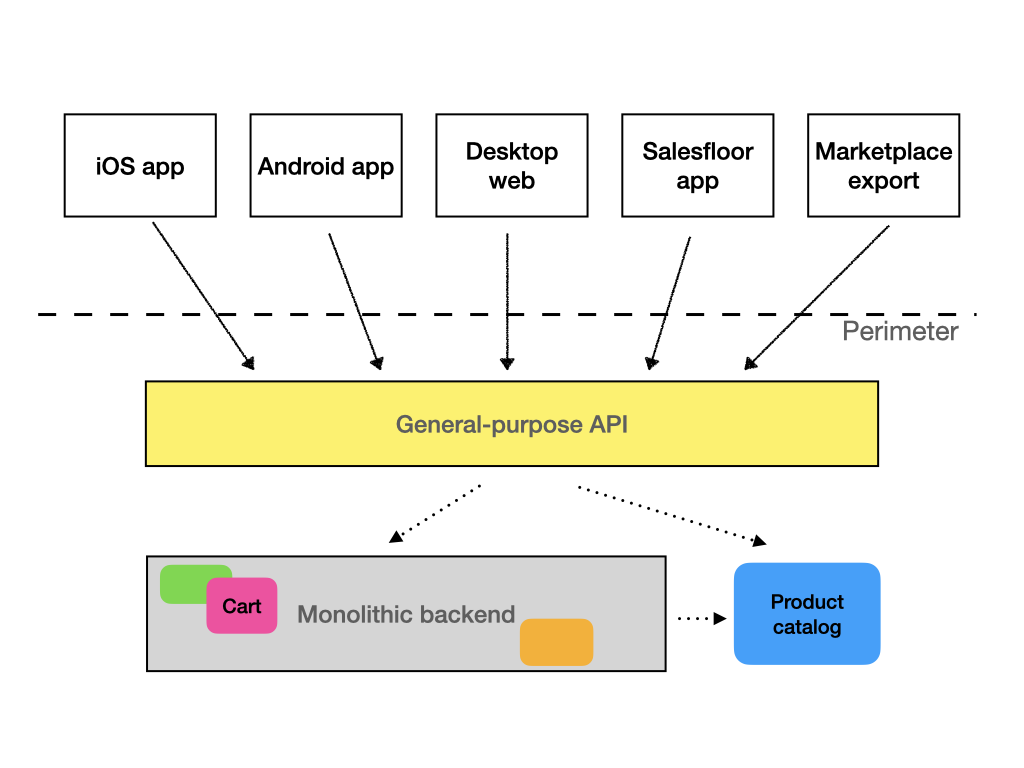

Such a complex product catalog can be built as a separate service. All user interfaces and external systems are then converted to use this service with it’s common API. I have also seen legacy systems converted into such service by adding an API, which will expose some objects and methods from the monolithic system. This is actually not a bad strategy for transitioning into a full service oriented architecture, but you have to make sure it does not stay this way forever.

This approach, relatively simple as it is to implement on the service side, has it’s own problems. Because the API is used by everyone, it has to provide all the data and all the methods everyone might ever need. That means it will be anything but “micro” and more importantly, the consumers of this API (think frontend developers, for example), will have to learn a much more complex interface. When we add the need to communicate with clients who speak other serialization and call mechanisms, such as gRPC or SOAP, the service can become very bloated very quickly. The consumer also usually gets more data, than is strictly necessary for what it wants to do, just because someone else might need it and creating a special endpoints for each consumer type would be tedious and, again, increase the size of the service and interface. When the service is consumed over the internet, and especially slow internet such as mobile, this also brings frontend performance issues and drains batteries.

It’s what I call a monolithic interface.

Interface segregation

The view from the consumer side is different. Ideally, each consumer would get a special interface, suited for it’s needs and providing only the data and methods it needs and nothing more. One consumer does not even need to know about the other versions of the API. This would be efficient not only because it reduces the cognitive load of developers on the consumer side, but also for performance reasons mentioned above.

This is what we call interface segregation.

API gateways to the rescue?

One of the common capabilities of most API gateways is the possibility to modify the messages in transit. You can remove some stuff, rename fields, even convert a gRPC service to HTTP one. So it looks like a good place to achieve the segregation.

It’s certainly possible to do, but I would not recommend it, except in specific cases. The gateway often has a different style of configuration that the code it exposes. But the main concern is with responsibilities. Most often, the gateway is managed by a different team from the one that makes the API it exposes. It often is managed by an ops team, rather than a development team. Self-service config changes are rarely possible. It introduces a very tight coupling between teams, which is not something you want.

Utilizing API gateway can make sense when you have just one team, that can manage changes across the whole stack. This, however, is not very common, because this also probably means, that your needs are fairly simple and a monolithic system would be a right architectural choice.

BFFs

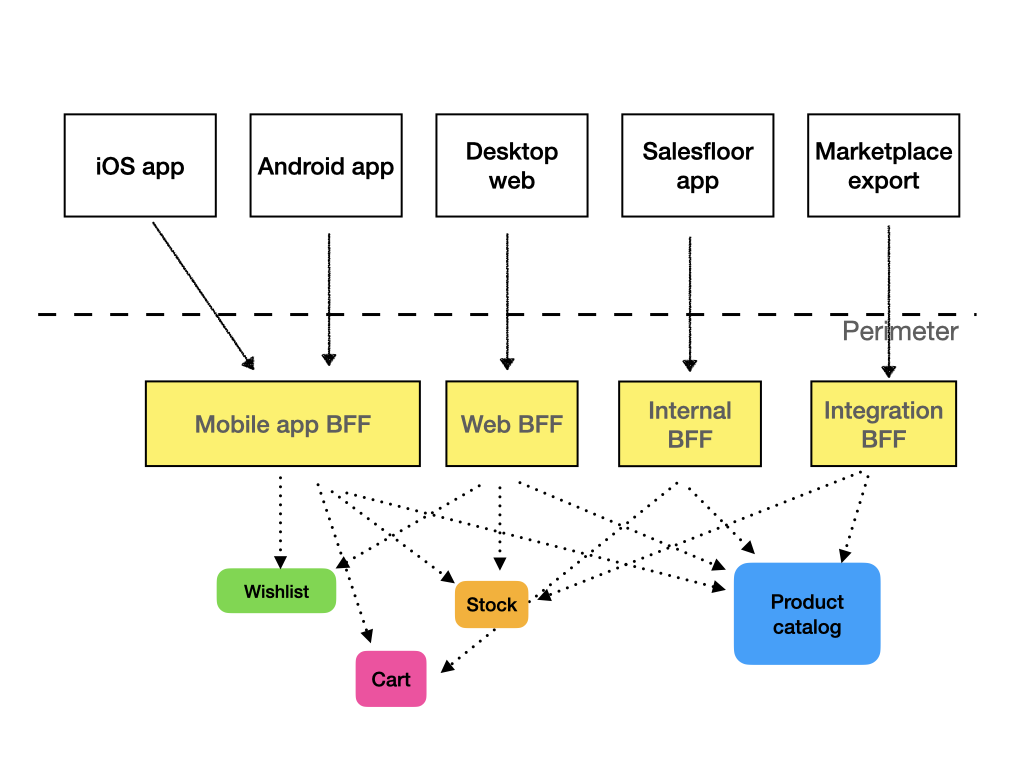

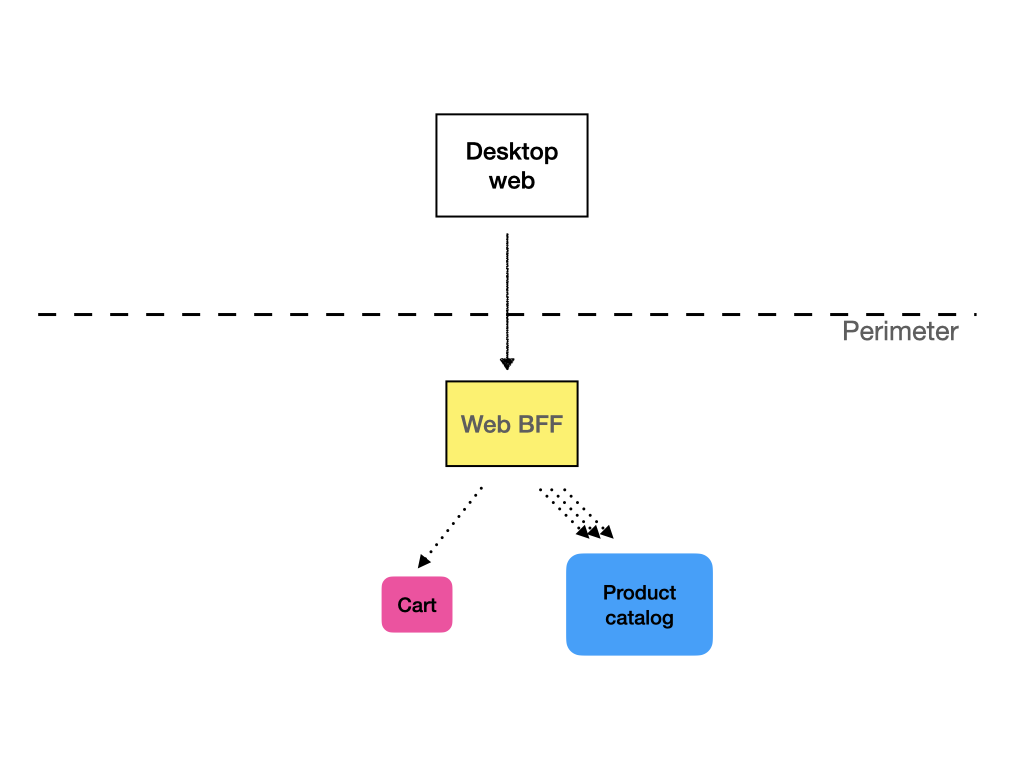

If API gateways and monolithic interfaces are usually not a way to go, what is? The answer is dedicated Backed-for-frontend, or BFF. For each class of clients, or even for each individual client, we create a separate API service, which presents the data in a way that is convenient for the consumer and only contains the methods used by the consumer. It can be much leaner than a general purpose API and change more quickly.

Organizationally, it makes sense to put these BFFs as close to the consumer as possible. For example, your web frontend team can maintain the BFF for web API. If you have a mobile dev team, they can manage the mobile app API. If you have separate Android and iOS development teams, it may even make sense each of them have a separate BFF. You will have some duplication, but bear in mind, that the BFFs should be very lightweight, without any business logic.

You might be tempted to abstract common functionality of these BFFs into a shared library. I mean things like input sanitization, logging, tracing. There is a very fine line here though, which is easy to cross and ends up in tightly coupled mess. I have a bad experience with things like creating a common HTTP client library, that does a bunch of extra stuff. These things have a tendency to become bloated, because everyone adds their stuff there and it can create a very tight but mostly invisible coupling between services. Suddenly, deploying a new version of one service means some other service breaks (when dependencies are not handled strictly enough) or needs unwanted refactoring. Things like request logging and authentication are also usually better handled either on the perimeter layer (smart proxy) or via a service mesh.

Sam Newman describes the BFF architecture pattern in his in-depth article, so I recommend you go check it out.

Service composition

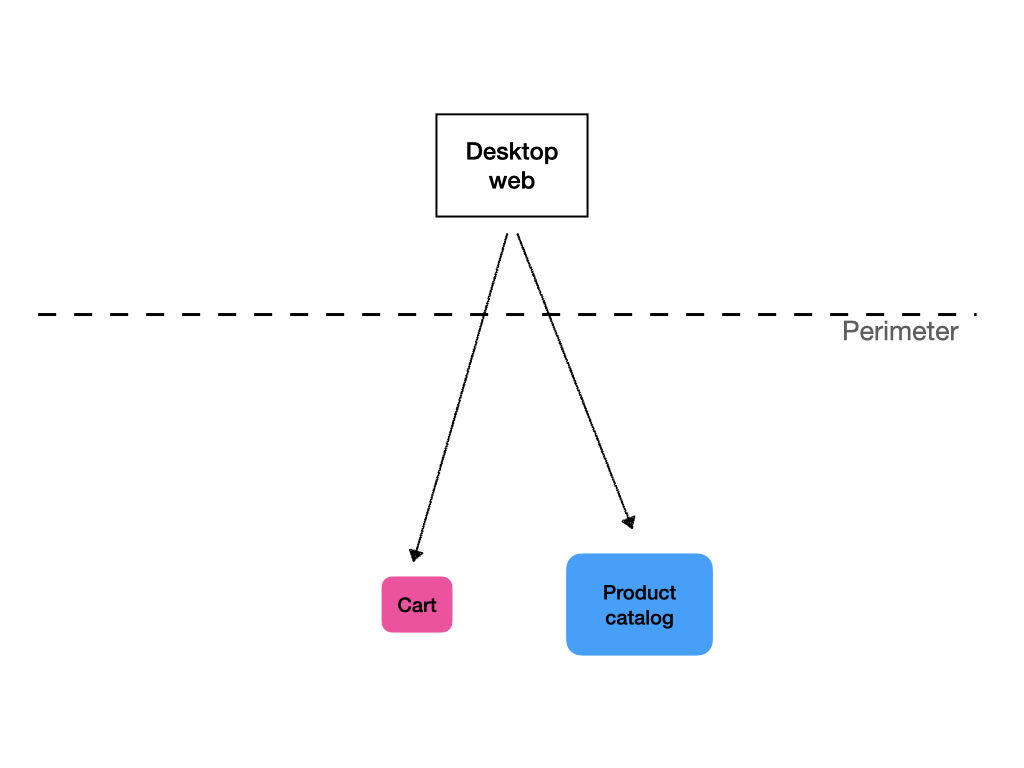

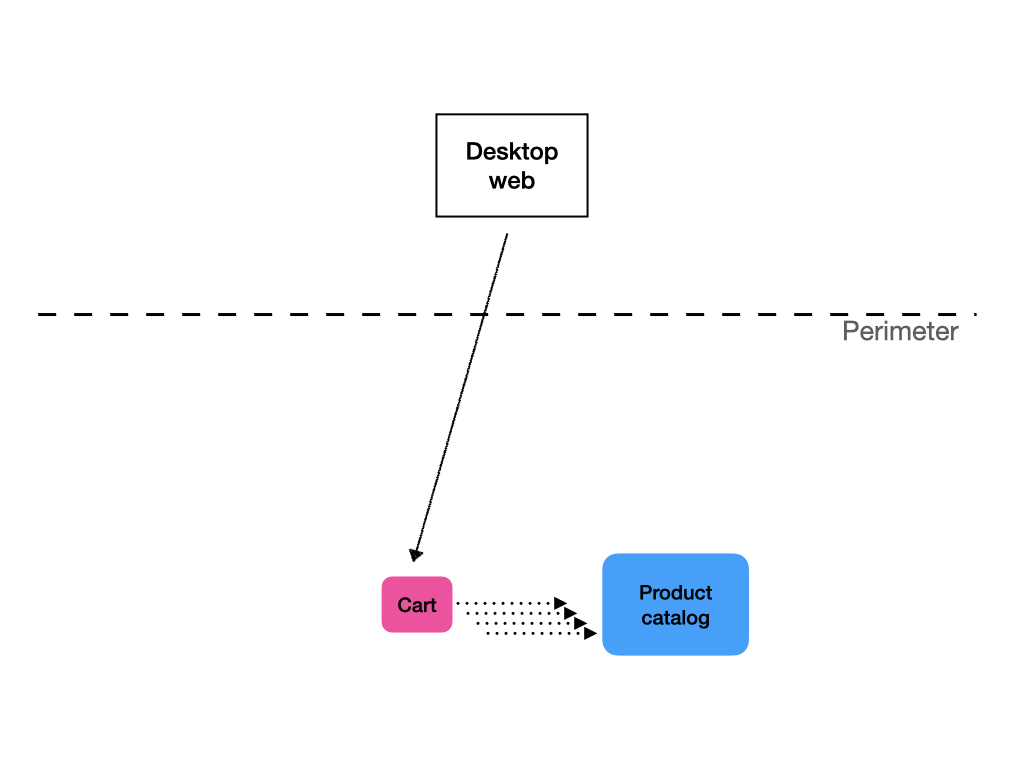

One of the roles a BFF can perform is composition of service calls. Let’s say you have a shopping cart service and product catalog service. When you display the contents of a user’s shopping cart, you first call the cart service to get a list of product IDs with a quantity. Then you need to call the product catalog to get detailed data on the products, such as their names and pictures.

One way to do this is on the frontend. However, when we are talking about apps delivered over the internet, this incurs a heavy latency penalty. If the roundtrip from client to server is 300ms (not unheard of for mobile networks), even with instantaneous server response, you are looking at 600ms response time to get the data needed to display the page. And I am not even talking about the fact that after you get the product data you have to request images and do another roundtrip to receive them. Sure, you can use some fancy stuff like placeholders and progressive enhancement, but the product data is pretty darn important so without it, the screen might be mostly unusable. If you are building an internal app, where it’s expected that it will be consumed over local network with sub-millisecond roundtrip, it’s probably an OK way to do this. Otherwise, your app will provide a poor user experience.

When most calls to the cart service result in subsequent calls to the product service by the client, it makes sense that the API returns the cart data enriched with the product data. That way, the client needs to do just one round trip.

One way to achieve this is with chaining the services themselves. In this scenario, the cart service would call the product service and use the returned data to enrich the response.

The other way is to do this in the API service. This is again where segregated BFFs make sense, because a generic API would probably either enrich the data much more than necessary, with performance implications, or it would have to provide a way to the client to specify what data it wants, adding complexity and making the service difficult to learn.

Bridging the age gap

Interface segregation is also a useful pattern, when you are building a new micro-service ecosystem, but have to integrate with legacy systems and services. Let’s say you start to build a modern infrastructure interconnected by a service mesh, such as Istio or Consul. At the same time, you have services outside of this infrastructure, that still need to talk to the new ones. Building BFFs for these new services can be a good way to bridge these two worlds. Because the BFF should be dedicated to a specific client, or class of clients, you can retire these APIs as soon as these legacy services are rewritten into your new infrastructure. If you did one generic “legacy” API, I can pretty much guarantee that you will maintain it forever.

Conclusion

Interface segregation draws from the principles of micro-services and adapts them for API design. It helps build lean efficient interface for your services, pushing the development closer to consumers. It can help to improve performance of the services, especially over mobile networks, while keeping the services smaller. Same as micro-services, it makes sense in larger environments with multiple teams by enabling them to be more independent and move quickly.

Comments